In 2014 I was commissioned by New Adventures in Sound Art to do an archival radio show and write an essay about "24 Hours of Radio Art" - an annual event that I started in the 90s with Bill Mullan, Adam Sloan, and Bobbi Kozinuk.

"24 Hours of Radio/ART" began in the summer of 1992 during the Canadian National Campus and Community Radio Conference held in Vancouver. The idea was to produce a twenty-four-hour radio art event - a radio station that was completely devoted to live creative work and experimental audio art. In effect, we asked the question: "What would happen if your local pop-radio station suddenly changed to an all audio-art format?"

"Radio with Everything at Hand" takes a look at the first four years of this event - an event that continues to this day, happening every year on January 17th on CITR FM, the campus radio station at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. The DJs and artists involved with the early editions of "24 Hours" used voice, turntables, CDs, cassettes, DAT, reel-to-reel tape loops, electronic instruments, samples from TV and cinema, scrap metal, oil drums, and field recordings to create massively layered walls of noise and more subtly layered waves of ambience. This episode of Cross Waves explores this history through commentary and excerpts form the original radio shows.

You can listen to the radio program on NAISA's SoundCloud channel.

Radio with Everything at Hand - produced January 2015.

Notes on the Cross Waves Radio Show

The program for NAISA radio for January 2015 was produced by Peter Courtemanche and Bill Mullan. It features selected works from the first four editions of "24 Hours" with commentary about the radio shows of the time. Writing and voice by Bill Mullan. Selections curated by Peter Courtemanche.

Introduction:

1. Origins or where it all began (4:50) by Bill Mullan

with extracts from early AVN Radio shows (1988 and 1990) and the Noise Day Promo Cart 1992 (0:58)

2. The Truth Channel 1992 (4:04) by Bill Mullan (tape and vinyl manipulation)

Set One:

3. Pariah 1992 (1:46) by Diana Arens (metal and voice) and June Scudeler (metal)

4. Noise of Change 1992 (7:14) by Don Chow (tape and beats) with sounds from Kelly White and Judy Radul

Set Two:

5. No Boundary Condition 1992 (7:47) with Pete Lutwyche (guitar), Adam Sloan (tone generator), and Jane Tilley (four track tape)

6. Intermission 1992 (Station ID from 1992) (1:38) by Bill Mullan

7. Free for All 1992 (7:18) with Diana Arens (voice), Bill Mullan (voice), Matt Richards (voice and effects), mixed by AVN and Adam Sloan

Set Three:

8. Radio on Radio/WENR 1992 (2:08) by Bobbi Kozinuk (hand-built 1 Watt FM radio transmitter and ghetto-blaster)

9. G42 Productions 1992 (4:45) by Patrick Devine and Scott Fraser (tape loops)

10. Live Radio without Human Intervention 1992 (5:44) by Adam Sloan (cd loops)

Set Four:

11. Toxic Option Syndrome 1992 (9:28) by Adam Sloan (tape and CD manipulation)

12. No Boundary Condition 1992 (3:10) by Pete Lutwyche (solo guitar)

13. No Boundary Condition 1992 (8:00) by Jane Tilley (four track tape)

Set Five:

14. Mass Produced Objects 1996 (2:00) by Judy Radul (voice and multitrack tape)

15. Everything U Know Is Wrong 1992 (6:11) by Pat Mullan (tape and vinyl manipulation)

16. Boris Bop 1992 (7:03) by Matt Richards (tape, voice, guitar)

17. Revox Duet 1992 (1:07) by Anthony Hempell (Revox PR99) and Adam Sloan (parametric EQ)

Set Six:

18. Gigablast! 1992 (10:31) by Andrea Cserenyi (tape and vinyl manipulation) with contributions from Larry Mud and the Sensuous Leper

19. Gigablast! 1993 (8:58) by Andrea Cserenyi (tape and vinyl manipulation)

Set Seven:

20. Noise Day ID 1993 (1:28) by Bill Mullan (with samples stolen from Gregory Whitehead)

21. Christopher Speener-Lowe 1992 (0:56) analog synth

22. Sound of Reality 1992 (4:10) by Anthony Roberts (tape and vinyl manipulation) and Michelle LaFlamme

23. Sound of Reality 1993 (2:30) by Anthony Roberts (tape and vinyl manipulation)

Set Eight:

24. Michele Frey 1996 (7:58) Michele records her journey from Gastown to the Western Front for Art's Birthday

25. Sound of Truth 1996 (6:02) by Bill Mullan and Anthony Roberts (tape and vinyl manipulation)

26. Truth Channel 1994 (parts I and II) (6:08) by Bill Mullan (tape and vinyl manipulation) and Rolf Wilkinson (on drums)

Set Nine:

27. Rolf and AVN 1994 (19:40) by Rolf Wilkinson (drums) and Absolute Value of Noise (tape and vinyl)

Set Ten:

28. The Last Show 1994 (5:25) by Bobbi Kozinuk (field recordings and sound effects records)

Bill Mullan is a Vancouver based writer, radio DJ (and producer). His past media adventures include magazine publishing (and editing), a few thousand hours of radio programming (CBC-2, campus and community), various screenplays, film and video productions, and, of course, non-stop sonic explorations. He also drove cab for a while. Randophonic is his current radio show (airing weekly c/o of UBC's CiTR.FM.101.9). In November 2013, he received his MFA diploma from UBC's Creative Writing program for Superlative Noise, a work of "sonic fiction".

The cast of the first four editions of "24 Hours" included: Diana Arens, Hank Bull, Shawn Chappelle, Don Chow, Peter Courtemanche, Andrea Cserenyi, DASZ, Patrick Devine, Scott Fraser, Michele Frey, Colin Griffiths, Ken Gregory, Anthony Hempell, Antonia Hirsch, Kathy Kennedy, Bobbi Kozinuk, Michelle LaFlamme, Pete Lutwyche, Bill Mullan, Pat Mullan, Judy Radul, Matt Richards, Anthony Roberts, John Ruskin (Narduar the Human Serviette), June Scudeler, Adam Sloan, Christopher Speener-Lowe, Jane Tilley, Sarah Toy, Zainub Verjee, Lori Weidenhammer, Rolf Wilkinson, and Cece Wyss.

Introduction

by Peter Courtemanche / Absolute Value of Noise © 2015.

The college radio studio of the 1990s was a place at the crossroads of social and technological change. It was the end of the Cold War and the beginning of the New World Order; we were in an economic recession that had been going on since the 1980s and showed no sign of ending anytime soon; many things were wrong with the world but at the same time there were rays of hope as issues of rights for visible and invisible minorities were making their way into a much larger spectrum of the overall social consciousness. There was a sense that this growing awareness could eventually infiltrate the shadowy depths of conventional power, a sense that we could eventually move from (what Robert Filliou called) a "political to a poetical economy."

My world was one of machines and sound: radio, recording studios, and performance spaces. I worked part time and spent as many hours as I could doing radio, writing, and volunteering at the Western Front (an artist run media production centre). For me, the early 1990s was a time to recycle and reinvent, to find discarded materials and equipment that could be repurposed and used to make something new. It was a time to hang-out and collaborate with other artists. It was a time to challenge the conventions of radio and do crazy, inventive, and often purposefully annoying (anti-social) sonic interventions on-air.

At CITR, the "giant" analog machines of the past were slowly being replaced by smaller consumer technologies and the digital machines of the future. The studio sported turntables, cassette decks, CD players, reel-to-reel machines, a voice-over booth, and a user-friendly patch bay that enabled DJs to plug in their own portable equipment. When you walked into the radio studio you were confronted by three walls of sound machines. You could throw on a vinyl record, turn 180 degrees and setup a tape loop, twist back 90 degrees and add a cassette to the mix, and then open up a microphone in the voice booth. It was natural to be spontaneous, to add something to the mix simply because the equipment was there, it was silent, and you could bring it to life. Annual fees paid to Canadian performing rights organizations allowed the DJs to take material from records and CDs and play with it on-air without fear of copyright infringement. It was an ideal environment for audio collage art, all happening at a time when technology was shifting from analog to digital, and at a time when "home taping" was the major means of affordably collecting and sharing sound, music, television, and movies. You could spend hours in the studio fashioning an elaborate cut-up; you could drag an oil drum and some scrap metal into the voice-over booth; you could wander along the industrial waterfront with a microphone and a cassette recorder. DJs used "everything at hand" to create massively layered walls of noise and more subtly layered waves of ambience. It was a time just before the computer screen took over the broadcasting and production worlds and narrowed the focus of control to a single small rectangle (all be-it a very interesting rectangle ..).

NOTES and Thoughts on the History of 24 Hours of Radio Art

by Peter Courtemanche / Absolute Value of Noise © 2014.

(1) Origins

It's early 1990. The radio station is in disarray. Dead air. Wires are lying all over the floor of the studio; stripped, bare leads crossing bare leads. The only thing the audience can hear (if there is any audience left) is Rapid Air Feedback. Somewhere in the chain of connections a ghetto blaster is tuned to 101.9 MHz (CITR FM) and its output is sent to the transmitter. We are broadcasting ourselves and at the same time rewiring the studio: not late at night, not with the power off, or the airwaves silent, or a tape deck looping through canned music. The sound is feedback, but not what you'd expect. It is set at the threshold, the lower threshold of sensibility, and instead of the harsh piercing of total annihilation there is a certain sense of purity; a form of tonal phase cancellation that is other-worldly, maybe from a different time and space; ambience and anxiety, simultaneous.

The artists are taking over the airwaves; they have gutted the studio in the pursuit of anarchic audio; a spiritual possession; the sound is the focus, the one and only reason for existence.

- Absolute Value of Noise, artist's journals, 1990

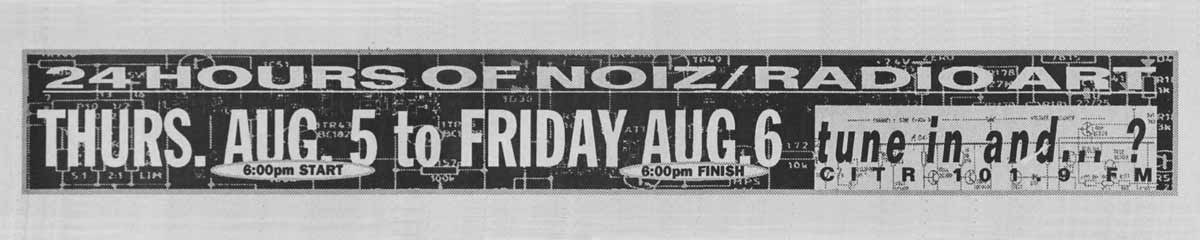

(2) Episode One

24 Hours of Radio/ART

began in the summer of 1992 during the Canadian National Campus and Community Radio Conference held in Vancouver. The idea was to produce a twenty-four-hour radio art event - a radio station that was completely devoted to live creative work and experimental audio art. In effect, we asked the question: "What would happen if your local pop-radio station suddenly changed to an all audio-art format?"

In 1992, there were a dozen or more sound-art shows on the air in Vancouver. There were two noncommercial FM stations: CITR (campus radio at the University of British Columbia) and CFRO (co-op radio in the downtown-eastside). New Sounds Gallery, Absolute Value of Noise, Noizi Radio, Sound of Reality, Gigablast, Truth Channel, and Home Taping International are just a few of the program names from this era. There were also many sound-art shows on other campus and community radio stations across Canada. The purpose of 24 Hours of Radio/ART was therefore to showcase this plethora of local audio-art practice and to provide a creative space to work with some of the radio-art programmers from other parts of the country (and a few from the United States) who were visiting the conference.

To a certain degree, Vancouver was known in the audio-art landscape as the land of the "aural assault." I wish I could remember where I read this. It was within an article about audio art in Canada that more or less dismissed Vancouver as being more noise than artistry, and went on to talk about Toronto and Montréal. Certainly noise was at the forefront of the Vancouver sound experience, but I think a more prevalent theme was the idea of "breaking the format of radio" by mixing, mashing, and not explicitly explaining the process to the listener. The radio programs that inspired 24 Hours of Radio/ART were heavily influenced by Negativeland, GX Jupitter-Larsen, Blackhumour, The Tape Beatles, Merzbow, and many other artists who worked with editing, noise, and layer upon layer of sound.

By doing live, chaotic radio that often suppressed "The Voice" (or more accurately "The Announcer"), we contradicted the rules of the radio "format." We didn't play public service announcements. We didn't talk about what we were doing. When we spoke, it was often to say something that added more chaos to the mix - a text, a reading, a cryptic sound poem. The listener was never enlightened as to the purpose of the noise; that was something they had to figure out for themselves, and people would phone and write to express their opinions - loving, supportive, contrary, annoyed, filled with extreme hatred.

Drawing from this inclination to engage in the "endless collage," the first edition of 24 Hours of Radio/ART was broken into twelve shows that were intended to overlap. The programming was imagined as a continuous stream where distinct voices would rise out of the ether. The show hosts spent anywhere from ten minutes to half an hour overlapping, creating an "inter-show" collage in between programs. The text from the 2011 edition of 24 Hours of Radio Art on CITR references the "Exquisite Corpse" as a way to describe this process and its extension into a collaborative radio sphere on the Internet.

These audio-art projects bring to mind other vividly surrealist elements, namely the inter-active game known as "Exquisite Corpse." This was an activity that usually involves three or more artists (generally visual types) that would start a drawing or montage on a piece of paper. When that artist was finished the paper was folded back or covered so that the next participant could not see what image came before. When the entire piece is finished, an amazingly bizarre picture is presented for the enjoyment of the group. When several stations (or even multiple people in the radio studio) are involved in radio-art and sharing audio over the internet, we have in essence, an audio version of an Exquisite Corpse. Combined with the surrealist's interest in random or spontaneous creations well, I'm sure the tie-in is all too obvious. Not to say that 24 Hours of Radio Art is all about noise. No. The day is about art and other arts have been known to broadcast. Poets and live musicians have graced the studio with their original contributions. The familial links of the creative arts are concrete and incontrovertible.

- Luke Meat (24 Hours 2011)

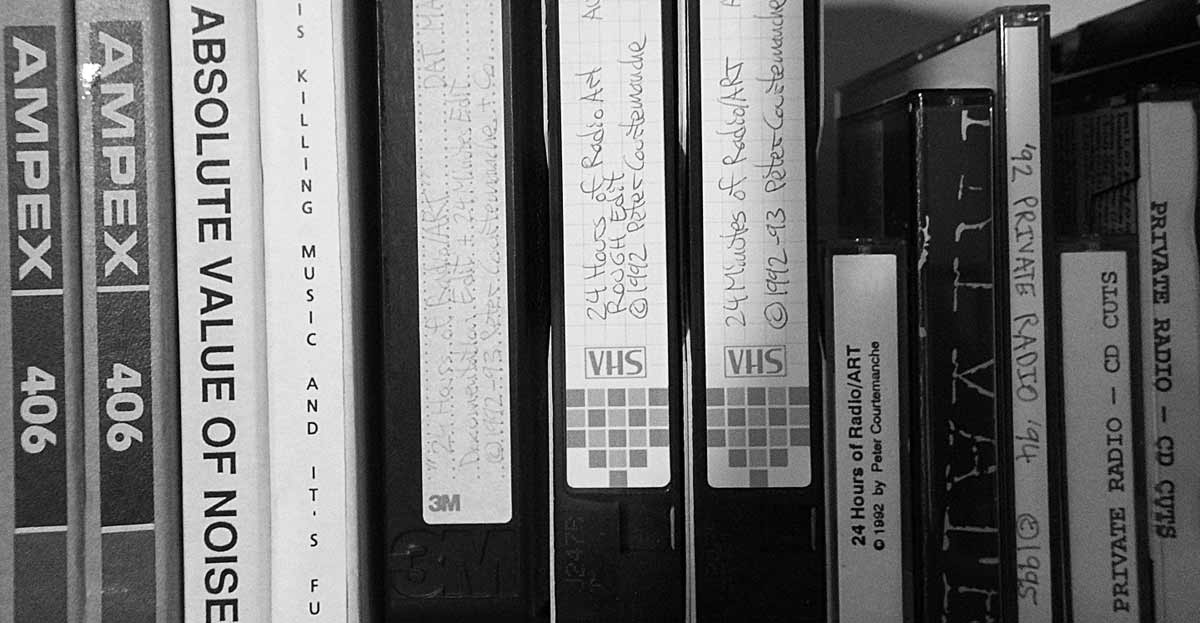

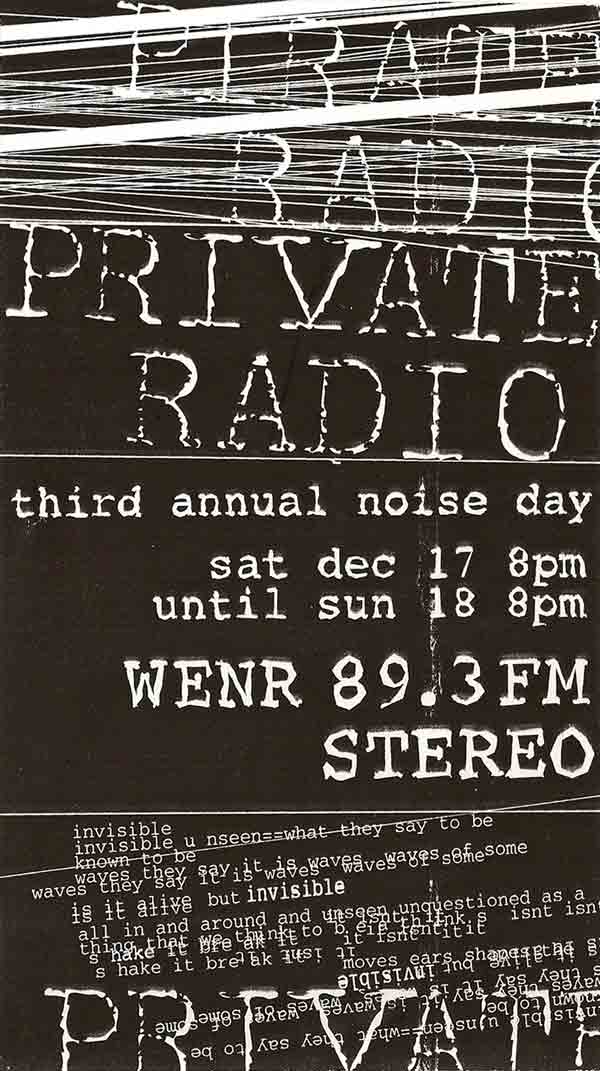

(3) Private Radio

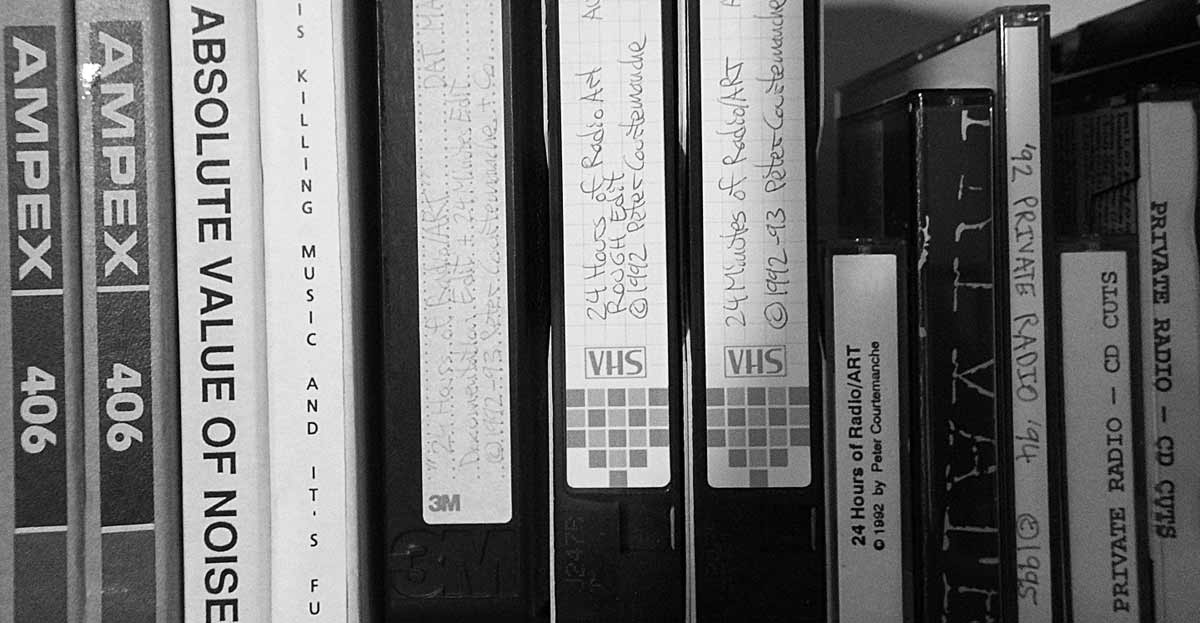

I produced the first four episodes of 24 Hours of Radio/ART in collaboration with Bill Mullan, Adam Sloan, and Bobbi Kozinuk. The first two events were hosted by the campus radio station CITR FM. The following two were hosted at the Western Front and broadcast on WENR FM 89.3. In late 1996, there was a very limited edition cassette release of program selections from all four episodes, and this was released with the title Private Radio.

Bill Mullan coined the term "private radio" as an alternate term for pirate radio. Bill felt that the connotations of "pirate" didn't really suite the reality of low-power, homemade transmitters and their use in suburban North American culture. Certainly there was no real risk involved in using these transmitters. There was often no political agenda, and no desire to take down, attack, or avoid inclusion in the "state." Instead, the people building and using the transmitters simply wanted to have their own private radio station that could be operated from the convenient location of their apartment or bedroom. It was also true that these stations broadcast to a small audience, often one or two people, sometimes thirty or forty if a special event was advertised. So the name Private Radio seemed more descriptive of the home-brew broadcast scenario.

WENR 89.3 perhaps had a few more listeners then most private radio stations. It was located at the Western Front (an artist-run centre in Vancouver that became engaged in avant-garde practice in 1973). The WENR transmitter had a range of three or four miles in line of sight from the top of the building. It was wired by Bobbi Kozinuk. She and Brice Canyon, working together as the hot-dog duo The Wiener Twins, hosted many events and broadcasts from live shows in Vancouver. WENR 89.3 was promoted through flyers, special events, and even made it to the mainstream evening news. As a result, it had a cult audience, and activities on the intermittent radio channel would cause a flurry of word-of-mouth publicity.

Bobbi and I were both working at the Western Front in 1994, so we moved the annual 24 Hours of Radio/ART event to WENR 89.3 and made use of the audio studio and performance space at the Western Front to do a different kind of art radio. (The Western Front is housed in a building with a concert hall, a sound and video studio, a gallery, a kitchen, offices, and artist accommodations.) Having access to a large performance hall made it possible to do more live acoustic work with homemade instruments, voice, et cetera. It also provided room for an audience to sit around the periphery, and there was room for a social space (where the artists could hang out when they weren't on the air).

(4) Episode Four: 24 Hours Meets the Network (Internet and Telecom) and Art's Birthday

Wednesday January 17, 1996

24 Hours of Radio/ART (Volume 4) will feature one full day of radio programming. Hosted at the Western Front during the annual Art's Birthday celebration, the show will run from 12 am on the morning of January 17, 1996 until midnight the following morning.

This program will be part of a larger celebration of Art's Birthday which traditionally is a day devoted to international exchanges using telephone connections for audio, video-phone, slow scan, fax, e-mail, and in recent years Internet exchanges.

- Peter Courtemanche and Hank Bull (24 Hours 1996)

Following the death of Robert Filliou in December 1987, it was natural for an artist network event to form around Filliou's inventive idea of Art's Birthday. In 1989, the Western Front started to hold annual telecommunications-art events on January 17th. These events varied in scope from year to year, sometimes involving a few participating nodes and other times developing larger international networks. Connections between distant points used radio, fax, slow-scan video, and audio-only, long-distance phone calls. Many of these annual events involved Kunstradio and also other artists and Art's Birthday groups in Vienna and were most often done under the moniker of Wiencouver.

In 1996, the fourth edition of 24 Hours of Radio/ART was broadcast on WENR 89.3 FM from the Western Front and also took place on Art's Birthday. This was the first intersection between the idea of art (artists) taking over the radio waves and art having a globally celebrated birthday party. 1996 was also an exciting time on the Internet (which, for most people, was only two or three years old). There were a number of developers trying to use the Internet as a means of communicating sound and image as a way of conveying live events over the network. The most notable software of the time was CU-SeeMe (video conferencing) and RealAudio (audio streaming). We were still using dial-up services for the Internet at this time, and the 56k modem was able to handle one audio stream out and one audio stream coming in. It's amazing to realize that the CU-SeeMe chat worked with this low bandwidth, with the images updating infrequently, maybe once every one or two seconds. 24 Hours of Radio/ART used old and new communications technologies to gather an odd collection of sounds that were chaotically mixed and broadcast for the first eighteen hours of the event. Then, for the final six hours, we gave up the network, cooked a feast, and featured live radio by eleven local artists. The feast was an enormous sausage stew cooked in a four-gallon pot.

(5) Monster Audio

Private Radio has involved many connections with audio artists around the globe - on tape, on the telephone, and in person. Programming has included the rebroadcasting of shows from afar, live sound collage on-air using tape and turntables, and improvised performances with alternative instruments (including vacuums, lawn mowers, vibrators, chains, and oil drums).

This web-site is intended to deliver a low-fi, often chaotic version of the Private Radio experience directly to your home, via the Internet. Selections from the 96 hours of programming are indirectly accessible through the AUDIO MONSTER. This is a Java Applet that serves up a semi-random collision of sound sources. Let it run for an hour, a day, a week. New patterns will evolve, new sources will be added, your ears will be soothed and annoyed.

- Absolute Value of Noise (1998). "Monster Audio" was a generative audio program for the web that played various selections from the 24 Hours of Radio/ART cassette release.

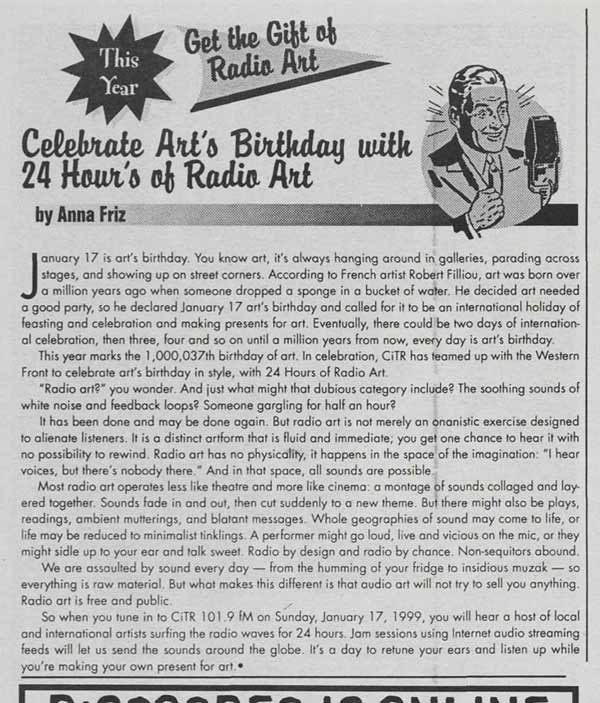

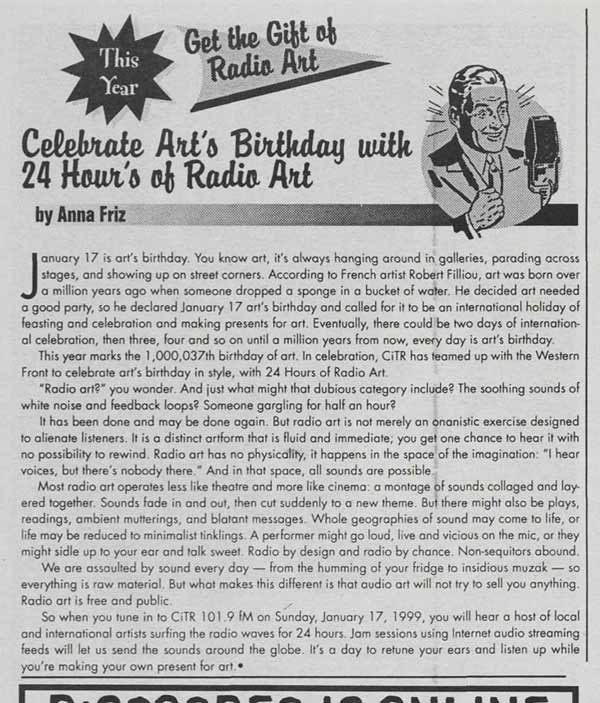

(6) 1999 Establishing a CITR Tradition: 24 Hours of Radio Art + Art's Birthday + Global Network

In April 1998, Matt Smith and Sandra Wintner arrived in Vancouver after a lengthy trip through the United States in a van. They became instrumental in dragging the Western Front into the era of the Internet, both in terms of developing a Web presence and in terms of streaming sound and image. Matt Smith (aka Firstfloor-Eastside) built an Icecast audio server in the back room and suddenly it was possible to stream events and interact with other artists who were using similar technologies. Matt was also instrumental in putting CITR FM online - initially as a stream that ran through the server at the Western Front, and then with a server of its own.

Anna Friz at CITR FM produced the 5th edition of 24 hours of Radio Art to coincide with Art's Birthday 1999. It became a collaborative venture between CITR, Western Front, Tetsuo Kogawa in Tokyo, and Kunstradio (who organized connections from Vienna and Linz). There were other participants, too, but the documentation is a bit sketchy. This was a major turning point for Art's Birthday as an electronic network, as the focus was shifted from telecommunications art (primarily slow scan and fax) to long-distance collaborative radio art using the Internet, and it set the tone for many future (2000-2014) Art's Birthday events involving CITR, Kunstradio, and the Western Front. This event happened at a point when long distance communication was abandoning the point-to-point telephone line and embarking into the Internet as a medium of more affordable and prolific communications technologies. ADSL and cable modems (the type of Internet connection prevalent today) had arrived on the scene, and suddenly it was possible for the average person (or low-budget artist organization) to send and receive multiple channels of sound and image.

The late night madness of art + radio spilled out from the broadcast studio and the two production studios, with artists entangled in gear on every flat surface at the radio station, while down the hallway the encoding computer was set up to send the stream to the Western Front server and out to the ether. 6AM PST found long-time Wiencouver ring leader Hank Bull at the helm of the Art's Birthday breakfast show engaging in a duet with media theorist Tetsuo Kogawa on the phone from Tokyo; later in the day CiTR programmers Industry and Agriculture jammed with an office full of collaborators at Kunstradio, Vienna. At one point online listeners from pirate Radio 100 in Amsterdam e-mailed to say they were rebroadcasting the jam.

- Anna Friz (2007)

An important aspect of 24 Hours of Radio Art is the way it has involved a diverse cross-section of radio programmers. These include CITR's regular volunteer programmers (who do shows throughout the year), who may or may not have previous interests or involvement in radio art or sound art; there are local audio artists (who may or may not have worked before with radio); and there are radio-art visitors from afar who happen to be in town during the event. This has provided a wealth of different styles and genres of programming over the years. It provides the opportunity for people with different interests and levels of experience to meet and collaborate or ignore each other as they choose. And from the listener's perspective - you never know what to expect next.

Following Anna Friz's departure from the radio station, 24 Hours of Radio Art was kept alive by Luke Meat and Bleek who organized most of the events from the turn of the millennium to 2011. Now it has become a fixture, managed by the current programming staff.

Every year, for some time now CiTR radio in Vancouver, and a few independent and college radio stations around the globe, have worked to give modern art a transmitter. The concept of giving art a birthday was introduced by French born artist/peacenik Robert Filliou (associate of John Cage, by the way). In 1963 he asserted that 1,000,000 years ago, there was no art. But one day, on the 17th of January to be precise, Art was born ... when someone dropped a dry sponge into a bucket of water. Filliou had lofty ideas floating around inside his skull about "relative permanent creation," an exercise in inner peace to be directed outward and into world peace. A continuing playful anarchy as a way of rejecting "the fascism of the square world," the world which refuses to break free of conventional wisdom and the inevitable war it falls into again and again.

- Luke Meat (24 Hours 2011)